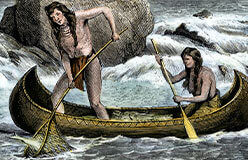

Oregon’s Native Americans are survivors. They – and their cultures – have lived on for thousands of years.

They have survived the attack of diseases brought by Europeans. Being forcibly removed from their homelands onto reservations. Being excluded from government functions.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the goal of the U.S. government’s policy toward Native Americans was to assimilate them into American society (assimilate means to “fit in” or “blend in”). In the words of Ben Nighthorse Campbell (a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe and former senator): “If you can’t change them, absorb them until they simply disappear into the mainstream culture. . . . In Washington’s infinite wisdom, it was decided that tribes should no longer be tribes, never mind that they had been tribes for thousands of years.”

Today, Oregon’s Native Americans keep their culture alive by celebrating their language, their traditions. And themselves.