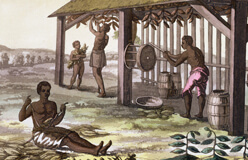

Early settlers risked their lives to set up new homes in unfamiliar territory. Every day, they worked to survive.

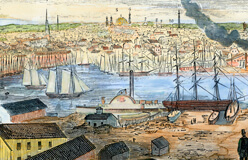

A generation later, their work paid off as Britain’s 13 colonies began to grow and flourish on North American soil. Roads began to connect one village to the next. Colonists learned from the Native Americans how to make it through the winter. Trade between the colonies began, and a reliable economy developed. Life was still hard in colonial America. As in earlier days, illness claimed colonists’ lives. And winters were long and harsh in the northern colonies. Survival, however, was no longer a surprise. Families planted their roots, and a new nation began to sprout.