Clara Barton knew that to live on her own she had to find a way to support herself.

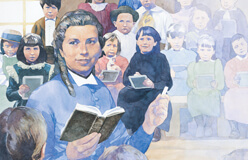

At first, she was nervous about becoming a teacher. Yet the more she thought about it, the more the idea appealed to her. She decided to try teaching and found that she liked it. And, she was good at it. Her concern for the poor led her to establish one of New Jersey’s first free public schools, in Bordentown.

In 1854, Barton looked for new challenges. She moved to Washington, D.C., and left the teaching profession. In Washington, she was appointed to a job at the U.S. Patent Office. (A patent is a document giving a person ownership of an invention.) Barton was one of the few women employed by the U.S. government. Breaking new ground for women was getting to be a habit for Clara Barton.