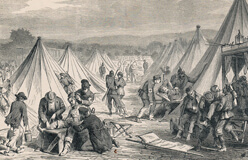

At the end of every war, the fate of many soldiers is unknown. Their families may wait for them to come home.

But many are already dead and buried in unmarked graves. At the time of the Civil War, the U.S. War Department had no system for tracing such missing persons. Barton proposed to open an office where people could write to ask about missing soldiers. With the help of the government, she believed she could track them down. But she needed government permission to examine military records. She also needed help writing letters and checking records. Did she find a way to put her plan into action?