The movement had a saying, “Free in ’63.” It meant that African Americans might finally have true freedom in 1963, 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

But it didn’t happen. Still, in the early 1960s, the civil rights movement won major victories in the face of bitter and often violent opposition.

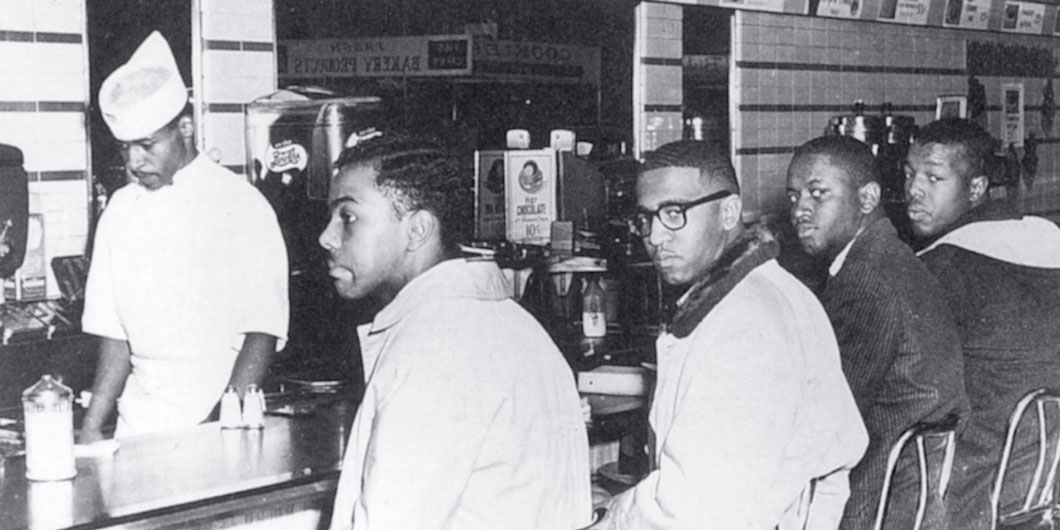

▲ On February 1, 1960, four college students—Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Joseph McNeil, and Franklin McCain—sat at a store lunch counter for whites only in Greensboro, North Carolina. They knew they wouldn’t be served, but they went back day after day. Others, black and white, joined them. In the two months that followed, similar protests, called sit-ins, spread to over a hundred cities in nine states. Out of the students’ efforts, a new organization was born. It was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”). By May of 1960, some lunch counters began serving African Americans.

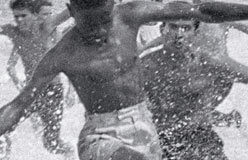

▲ The Supreme Court had outlawed segregated seating on buses and trains that traveled between states and in waiting rooms at stations. The civil rights group CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) decided to test the law and call attention to segregation. On May 4, 1961, 13 volunteers—black and white—set out on a “Freedom Ride” through the South. In Alabama, their bus was bombed, and mobs attacked them viciously. But the group accomplished its goal of forcing the U.S. government to uphold the Supreme Court’s ruling.

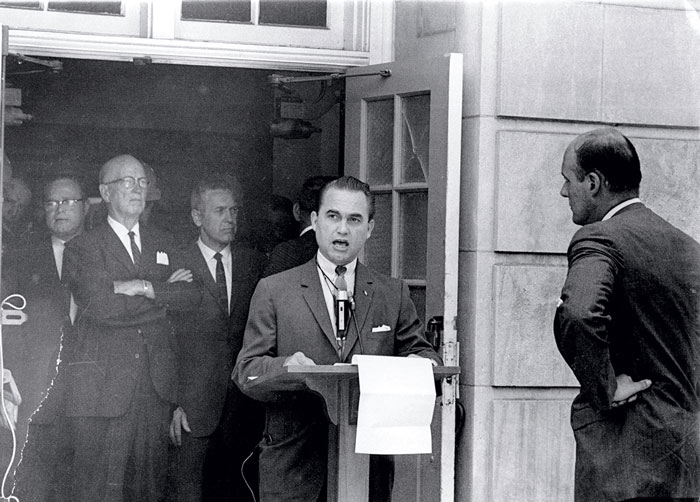

▲ The civil rights movement was making gains, but it was also enraging segregationists. In 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace (above) pledged to “stand in the schoolhouse door” to keep African Americans out of the University of Alabama. He did stand in the door, but when President John F. Kennedy took a firm stand to protect the two black students who were trying to register, Wallace backed down. In later years, Wallace apologized to civil rights leaders and called segregation wrong.

Before 1963, U.S. presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy (below) had confronted segregation reluctantly and haphazardly. On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy spoke on television about segregation as a moral issue. He said he would soon ask Congress to pass legislation to ban segregation. Less than six months later, Kennedy was assassinated. But his legislation was later passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. ▼

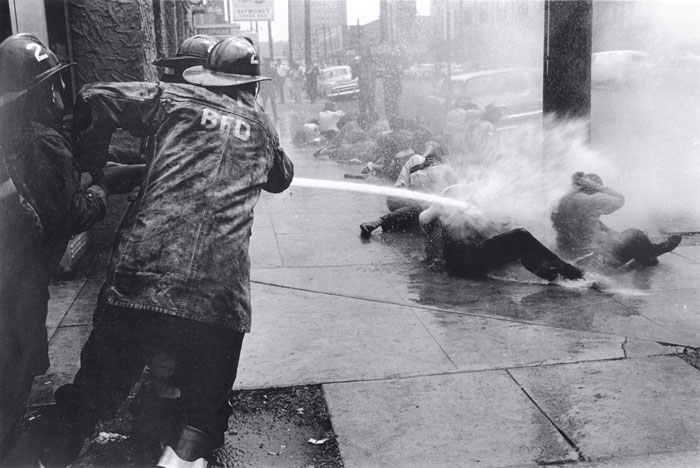

◀ On May 3, 1963, in Birmingham, Alabama, firefighters tried to dislodge demonstrators with high-pressure water hoses, strong enough to skin the bark from trees. The demonstrators, many of whom were young students, were sitting in protest against Birmingham’s segregation laws. They hoped that their nonviolent approach would serve as a model for other protesters.

▲ On August 28, 1963, about 250,000 demonstrators—black and white—participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. There were dozens of speakers, but the last speech of the day was the one that went down in history. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of his dream of freedom. “I have a dream,” he said. “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

◀ Sadly, many were not ready for King’s dream. On September 15, 1963, a bomb ripped through a church in Birmingham, killing Denise McNair, 11; Addie Mae Collins, 14; Carole Robertson, 14; and Cynthia Wesley, 14. Four suspects were soon identified. All were members of a Ku Klux Klan chapter. The first suspect was not tried until 1977. Two more were convicted in 2001 and 2002. The fourth died without ever being charged.