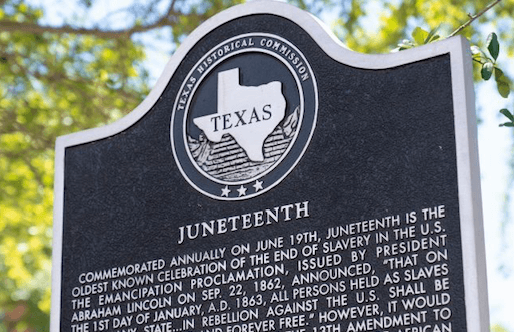

The movement had a saying, “Free in ’63.” It meant that African Americans might finally have true freedom in 1963, 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

That didn’t happen. Still, in the early 1960s, the civil rights movement won big victories in the face of bitter and often violent opposition.

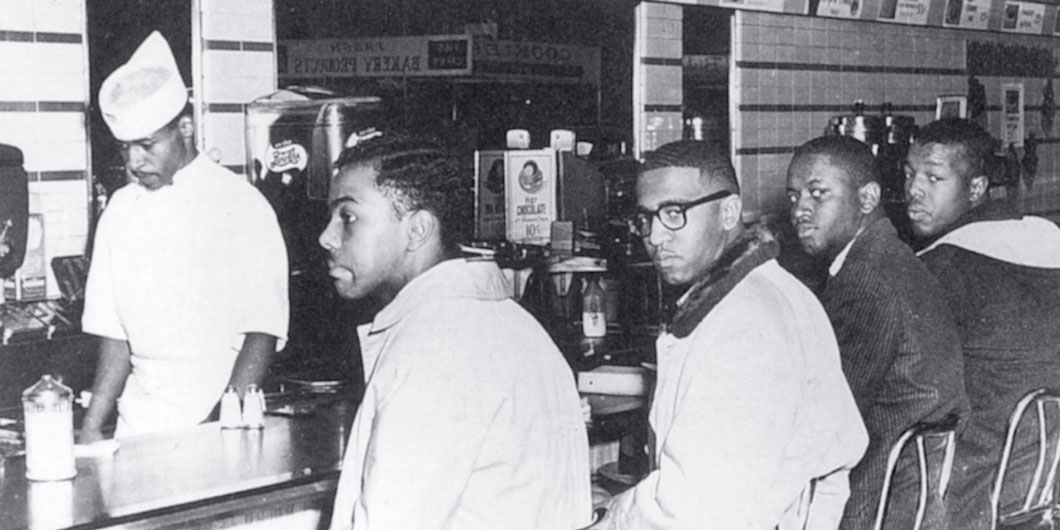

▲ On February 1, 1960, four college students—Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Joseph McNeil, and Franklin McCain—sat at a store lunch counter for whites only in Greensboro, North Carolina. They knew they wouldn’t be served. But they came back day after day. Others, black and white, joined them. In the next two months, protests like theirs spread to over a hundred cities in nine states. These events were called sit-ins. The students’ actions gave birth to a new group. It was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”). By May 1960, some lunch counters began serving African Americans.

▲ The Supreme Court had outlawed segregated seating on buses and trains that traveled between states. It also banned segregation in waiting rooms at stations. One civil rights group was CORE, or the Congress of Racial Equality. It decided to test the law and call attention to segregation. On May 4, 1961, 13 volunteers—black and white—set out on a “Freedom Ride” through the South. In Alabama, their bus was bombed. Mobs attacked them. But the group accomplished its goal of making the U.S. government support the Supreme Court’s ruling.

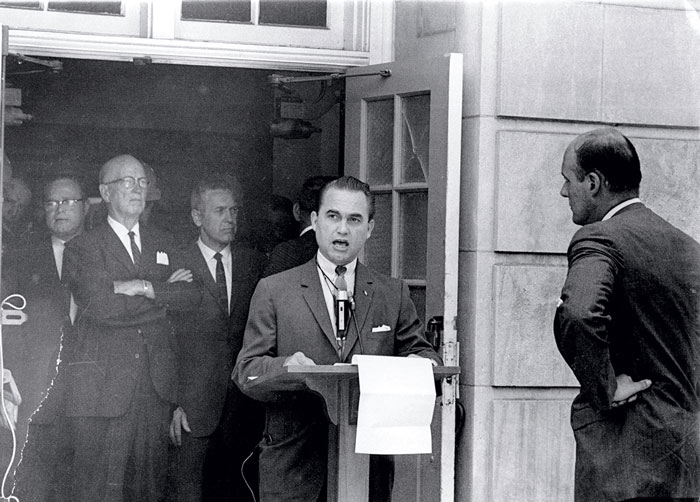

▲ The civil rights movement was making gains. But it was also making segregationists angry. In 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace (above) pledged to “stand in the schoolhouse door” to keep African Americans out of the University of Alabama. He did stand in the door. But he backed down when President John F. Kennedy took a firm stand to protect the two black students who wanted to register. In later years, Wallace apologized to civil rights leaders and called segregation wrong.

Before 1963, U.S. presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy (below) had dealt with segregation only when they had to. And they didn’t handle it in organized ways. On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy spoke on television about segregation as a moral issue. He said he would soon ask Congress to ban it. Less than six months later, Kennedy was assassinated. But his legislation later passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. ▼

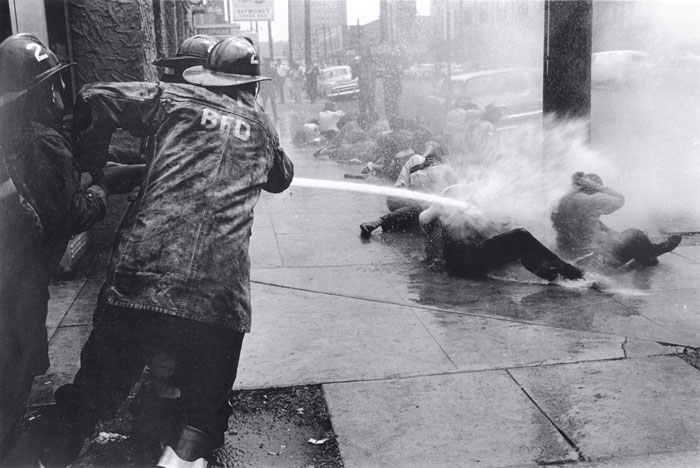

◀ On May 3, 1963, in Birmingham, Alabama, firefighters tried to remove demonstrators with powerful water hoses. The water pressure was strong enough to skin the bark from trees! Many of the demonstrators were young students sitting in protest of the city’s segregation laws. They hoped others would follow their nonviolent approach.

▲ On August 28, 1963, about 250,000 demonstrators—black and white—took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. There were dozens of speakers. But the last speech of the day was the one that went down in history. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of his dream of freedom. “I have a dream,” he said. “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

◀ Sadly, many were not ready for King’s dream. On September 15, 1963, a bomb ripped through a church in Birmingham, killing Denise McNair, who was 11, and 14-year-olds Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley. Four suspects were soon found. All were members of the Ku Klux Klan. The first suspect wasn’t tried until 1977. Two more were convicted in 2001 and 2002. The fourth died without ever being charged.