In the first half of the 17th century, England was creating colonies along the East Coast of North America. France was establishing New France to the west and north.

The governor of New France, Samuel de Champlain, sent teenage explorer Étienne Brûlé to venture farther west, to live among Indigenous peoples and to learn their culture and language. By 1622, Brûlé had made it all the way to Lake Superior. For the next 150 years, others followed. They came to explore, to trade, and, in the case of Jesuits, to teach.

▲ Most historians recognize Jean Nicolet as the first European to explore present-day Wisconsin. Perhaps his goal was to find a way to reach the Pacific Ocean. Perhaps it was to open trade relations with Indigenous peoples. In 1634, with the help of local guides, Nicolet traveled south along the western shore of Lake Michigan to Green Bay. A Jesuit priest and friend of Nicolet wrote this about one of his encounters with Indigenous peoples:

The news of his coming quickly spread to the places round about, and there assembled four or five thousand men. Each of the chief men made a feast for him, and at one of the banquets they served at least sixscore [120] beavers. The peace was concluded . . . and some time later . . . [Nicolet] continued his employment as agent and interpreter to the . . . satisfaction of both the French and the [Indigenous peoples].

In 1669, Claude-Jean Allouez set up a Jesuit mission among Indigenous peoples near Green Bay. (A Jesuit mission is a place where Jesuits, a group within the Catholic church, teach reading, writing, and religion.) His written records are some of the earliest. They include descriptions of the landscape. They also describe the customs and daily life of the Indigenous peoples he met.

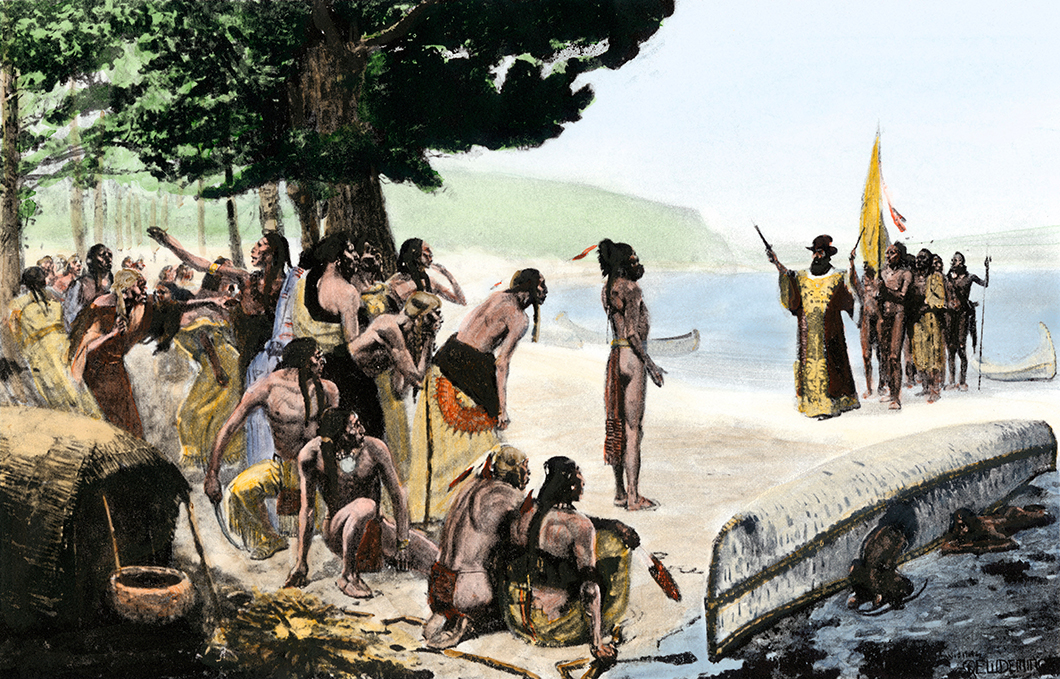

▲ Father Jacques Marquette was a Jesuit priest. Louis Jolliet was a French Canadian fur trader. In May 1673, the two set out on a four-month journey. It began at the northernmost point of Lake Michigan. They traveled along the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers to the Mississippi, which they followed all the way to present-day Arkansas. While Marquette and Jolliet were not the first Europeans to discover the Mississippi, they were able to show that the river emptied into the Gulf of Mexico and not the Pacific Ocean, as previously thought. Here is part of Marquette’s diary from the trip:

The [Wisconsin] river . . . is very wide; it has a sandy bottom. . . . On the banks one sees fertile land, diversified with woods, prairies, and hills. There are oak, walnut, and basswood trees; and another kind whose branches are armed with long thorns. We saw neither feathered game nor fish, but many deer, and a large number of cattle.

Here we are, then, on [the Mississippi River] . . . . From time to time, we came upon monstrous fish, one of which struck our canoe with such violence that I thought that it was a great tree, about to break the canoe to pieces. . . . We continue to advance, but, as we knew not whither [where] we were going . . . we kept well on our guard. We make only a small fire on land . . . to cook our meals; and after supper, we . . . pass the night in our canoes, which we anchor in the river at some distance from the shore.

Between 1712 and 1733, several conflicts, known as the Fox Wars, took place in eastern Wisconsin. The wars were between the Fox tribe (also known as the Meswaki) and the French, who wanted to control the Fox River so they could use it for the fur trade. In the end, the Fox were driven west of the Mississippi River. The conflict nearly wiped out the Fox. ▶

Kee-shes-wa, a Fox chief

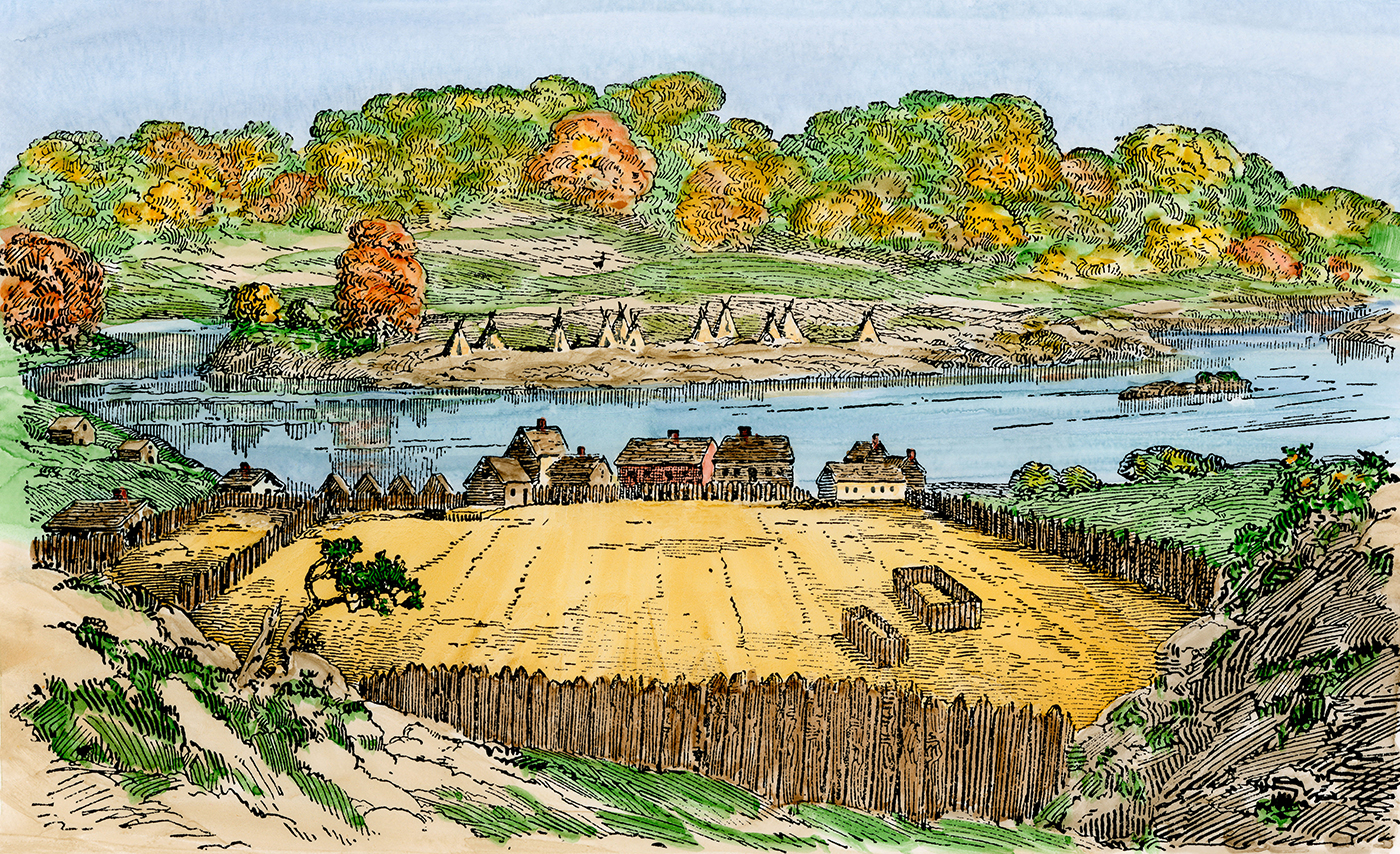

◀ Together with his father, soldier and fur trader Charles Michel Langlade established a trading post at Green Bay in 1745. At the time, Langlade was a teenager. For much of his young adult life, he fought to protect French territory in North America. During the American Revolution, he fought for the British, hoping to keep American settlers out of the region. After the war, Langlade returned with his family to live the rest of his life in Green Bay. Says Lisa Haefs of the Langlade County Historical Museum, “He . . . created the whole northern part of Wisconsin, as you know it.” For these actions, and for being one of the bravest pioneers of the West, the state of Wisconsin named him the “Founder and Father of Wisconsin.”

In 1754, Britain and France went to war in North America. The war is known as the French and Indian War. It was about which country would control land that included Wisconsin. Like many groups of Indigenous peoples, those in Wisconsin sided with the French. The war ended in 1763 with Wisconsin coming under British control. ▶

Northwest Territory, 1787

▲ When the American Revolution ended in 1783, present-day Wisconsin became a U.S. territory. Four years later, Congress passed a law known as the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. The law officially established the Northwest Territory, which included all the lands north of the Ohio River to the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi River to Pennsylvania. Specifically, the lands that would become Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and part of Minnesota.