The 1800s brought change to Wisconsin. Change for Indigenous peoples and settlers alike.

It changed from a land inhabited mostly by Native peoples to a destination for newcomers from Europe and the eastern U.S. From an economy based on fur trading to one based on mining, manufacturing, and agriculture. And from a territory to a state. Nineteenth-century Wisconsin was on its way to becoming a full partner in the history of the United States.

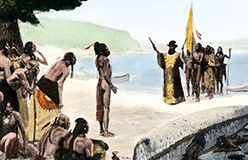

▲ In 1812, the United States was again at war with Britain. The fight was partly about Britain forcing American sailors to work on British ships. It was also about Britain siding with Indigenous tribes that challenged U.S. settlement. The only battle fought in Wisconsin during the War of 1812 was the Battle of Prairie du Chien. It took place in July 1814 at Fort Shelby (above). With the help of local tribes, the British took control of the fort after only two days. However, months later they were forced to leave when the Americans won the war.

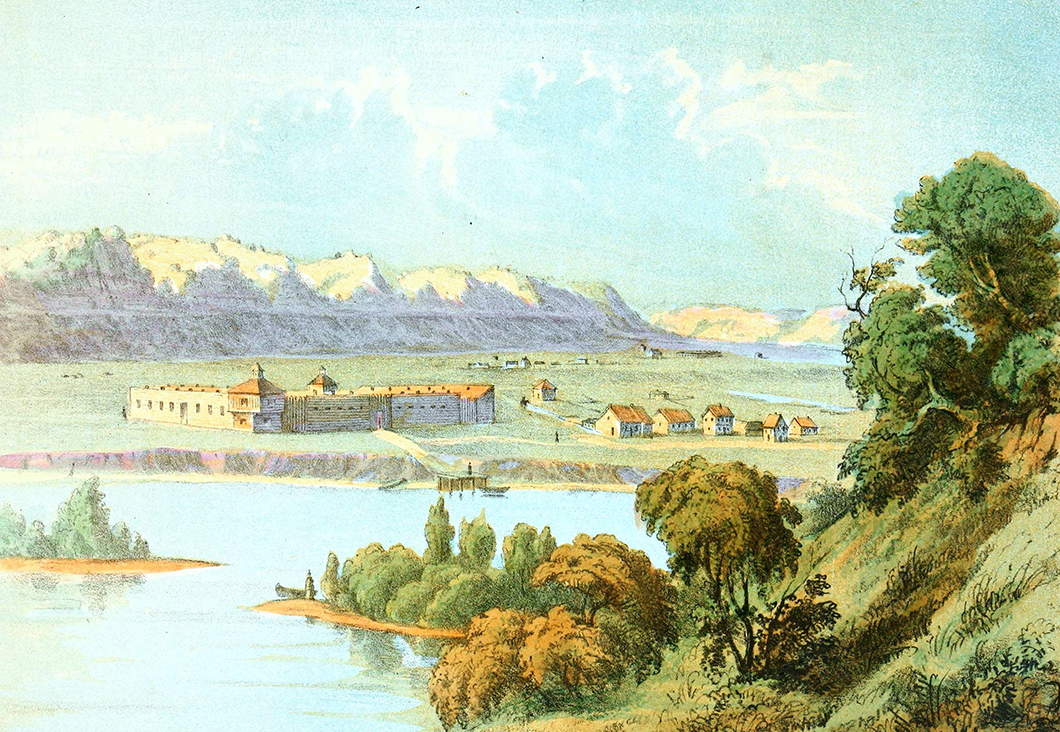

▲ In the early 1800s, the U.S. government set up Federal Land Offices in parts of the Northwest Territory, including Milwaukee and Green Bay. These offices offered cheap land in the region. They wanted to attract settlers, shopkeepers, and speculators. (Speculators are people who buy something in hopes the price will go up so they can sell it for more.) New towns were created. New economies like timber and lead mining developed. Land-grant universities that provided research and education to benefit the state were established. The University of Wisconsin is a land-grant university.

Reflection

Think about the Indigenous peoples of Wisconsin. What effect do you think the land offices had on them?

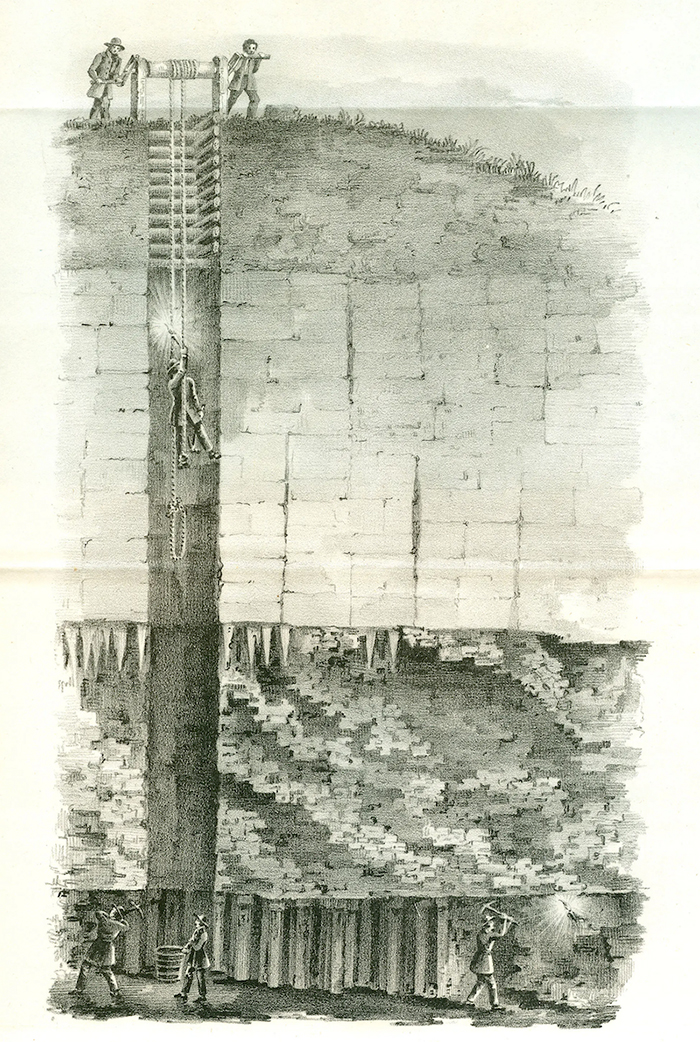

American settlers learned about the presence of lead in southwestern Wisconsin from Indigenous peoples. And they wanted it. Lead mining became even more popular than fur trading or farming. The Wisconsin “Lead Rush” of the 1820s and 1830s drew thousands of European and American prospectors. For living arrangements, many miners burrowed holes into a hillside. These reminded people of the kind of home a badger would make. It earned miners the nickname “badgers.” Later, Wisconsin was nicknamed the “Badger State.” ▶

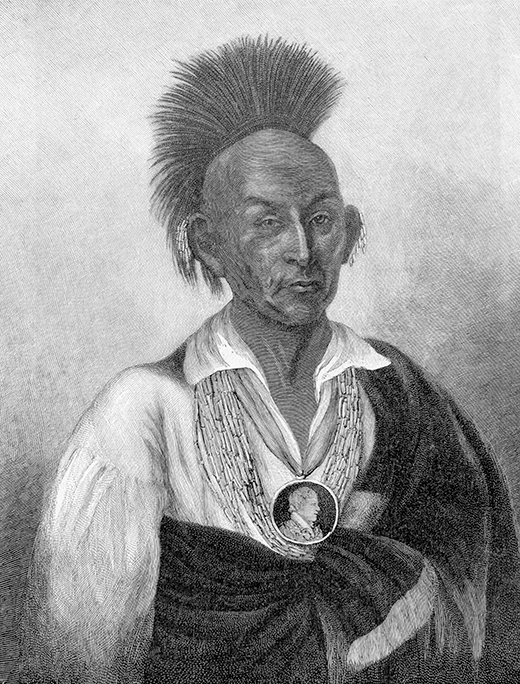

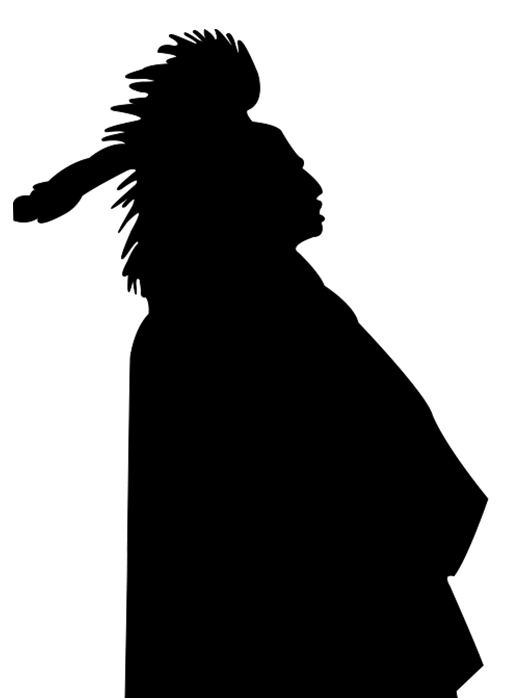

In the early 1800s, settlers wanted land. Land for homes. Land for farms. Land for mining. The U.S. government was there to help. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. The law forced Indigenous peoples to move west of the Mississippi River. Conflicts followed. The Black Hawk War of 1832 was one of them. At the time, Black Hawk (right) was war chief of the Sauk tribe. He led his people to fight against the U.S. Army and local militiamen in Illinois and Wisconsin. (Militiamen were citizens with some military training.) But his group was no match for the Americans. The Battle of Bad Axe near Victory, Wisconsin, on the banks of the Mississippi River, was the last battle between the U.S. government and Indigenous peoples east of the Mississippi River. ▶

◀ The Menominee lived in the dense forest of eastern Wisconsin. The forest provided everything the Menominee needed – food, clothing, wood for their homes and canoes, and medicines. The U.S. government wanted the land for farms. The Menominee chief, Oshkosh (left), understood that his people could not fight the U.S. government and win. He had little choice but to give up more and more Menominee territory. By 1848, the government wanted the Menominee to leave altogether and move to present-day Minnesota. Chief Oshkosh said no.

▲ In 1856, Chief Oshkosh convinced the U.S. government to preserve land along the Wolf River for his tribe. In their new home, they adopted a system that helped keep the forest healthy. One plan concerned how they harvested trees. They took out only old and weak trees, the ones that were dying. This helped keep the forest healthy. Today, the Menominee teach their ways to people in many parts of the world. It’s called sustainable forestry. Christopher and Barbara Johnson, writers for the magazine American Forests, describe it this way:

The Menominee view themselves as the forest’s stewards [keepers], never taking more resources than are produced within natural cycles so that the forest’s biodiversity can be sustained. They also believe that rewards can’t be measured in financial terms alone, but in environmental, cultural and spiritual values. . . . Today, Menominee Forest has incredible stands of old-growth trees. . . . ancient white pines at least 15 feet in circumference and soaring 200 feet into the sky.

Reflection

Reflect on the conflicts between Indigenous peoples and the U.S. government. Was one side more “in the right” than the other? How else could the conflicts have been settled?

▲ In 1836, Wisconsin became its own territory after decades of being part of other territories. The first capital was Belmont but it was moved to Madison the following year. The people, though, were not so sure becoming a state was a good idea. They thought they would end up paying higher taxes. Between 1842 and 1847, Wisconsinites voted against statehood four times. In 1847, they rejected the state constitution as it was written. Finally, in 1848, they approved a new constitution, and Wisconsin became our 30th state.

Check It Out!

Why did Wisconsin voters reject the 1847 constitution?

The 1847 constitution allowed non-citizens to vote. It allowed women to own property. It said the state government could not create banks or print paper money in bills bigger than $20. It also provided for a way to give Black men the vote. Wisconsin voters – all White men – said no and voted the constitution down.

▲ Arthur MacArthur Jr. was one of the soldiers from Wisconsin who fought in the Civil War. MacArthur and his regiment were at the Battle of Missionary Ridge in Chattanooga, Tennessee. (A regiment is a group of soldiers.) The battle was going badly for them. Soldiers were falling, including one who was carrying the regiment’s flag. MacArthur picked up the flag and held it high. “On Wisconsin!” he yelled. His call inspired thousands of soldiers to follow him. Together, they won the battle for the Union. MacArthur’s call also inspired friends William Purdy and Carl Beck to write the music and lyrics for “On Wisconsin,” a song heard at University of Wisconsin–Madison football games since 1909.