Free

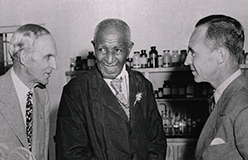

George Washington Carver accepted Booker T. Washington’s offer to be the director of agriculture at Tuskegee Institute. The year was 1896.

He remained there for 47 years, until his death in January 1943. That day in 1896 would change the course of his life. It would also change the lives of poor farmers in the South. And the economy of the whole region. As the story goes, it was so significant to Carver that he added “W.” or “Washington” to his name to honor Booker T.