The new Constitution was sent to the states, and each state was supposed to call a convention, where delegates would vote to ratify or not ratify the document. Then the real debate began.

Those who supported the Constitution were called Federalists. (Federal refers to a central government.) They thought the country would do better with a stronger central government.

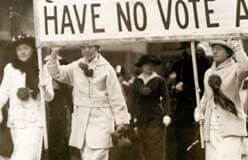

Those who were opposed to this idea were called Anti-Federalists. People had many reasons for being against the Constitution. Some thought a central government wouldn’t care about local issues, and some said it would overwhelm the states and take away the people’s rights. Other people feared the government would be taken over by “the few and the great,” while some said the president would have too much power. Others said the slavery clauses were immoral. The strongest argument against the document was that it did not state the rights of the people.