In 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

From 1964 to 1968, both triumph and tragedy were part of the civil rights movement.

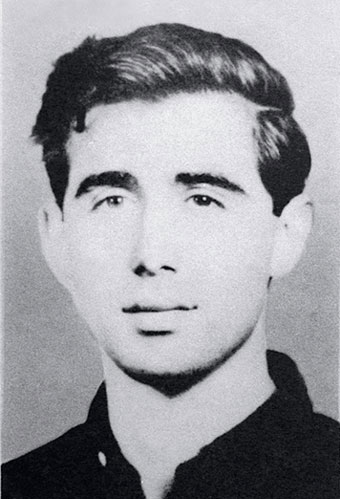

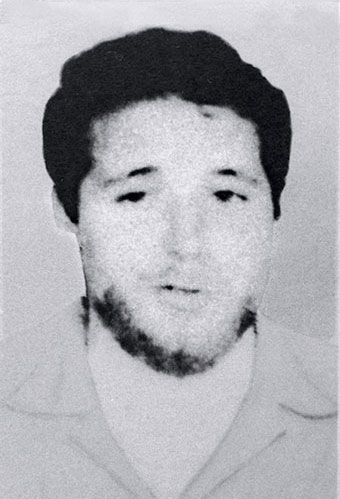

Andrew Goodman

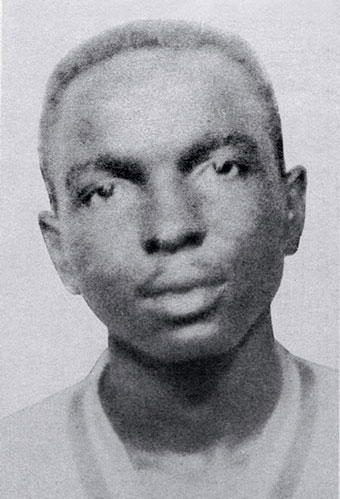

James Chaney

Michael Schwerner

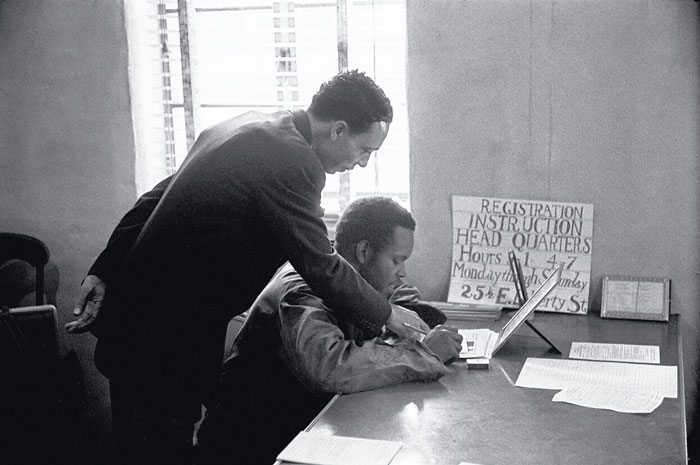

▲ When African Americans in the South tried to register to vote, they were often intimidated by white officials. They were forced to take “citizenship tests” that white voters did not face. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee took on the project of helping black people register to vote in Mississippi. In 1964, the group recruited students from the North to help with the project. That summer, Andrew Goodman went South and joined veteran civil rights workers Michael Schwerner and James Chaney. The three were beaten and shot to death by Ku Klux Klansmen. It was not until 2005—four decades later—that the state of Mississippi convicted the ringleader. ▼

On July 2, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He had pushed hard for passage of Kennedy’s bill. It outlawed segregation in restaurants, hotels, movie theaters, sports arenas, and other public facilities. It also banned job discrimination due to sex, race, religion, or national origin. A year later, Johnson also got Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It assured that African Americans were not denied their right to vote. ▶

▲ Early in 1965, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference joined a voter registration project in Selma, Alabama. The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and 250 adults were arrested for marching. When 500 children protested the arrest, they were arrested, too. A group tried to march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital, which was 54 miles away. State troopers on horseback used billy clubs, bullwhips, tear gas, and cattle prods to break up the marchers. When photos of the attack were shown on television, people, both black and white, from all over the country flocked to Selma. On March 21, 4,000 protesters started a march to Montgomery, this time protected by the U.S. military. They reached Montgomery five days later, on March 25. By then the number of marchers had grown to 25,000.

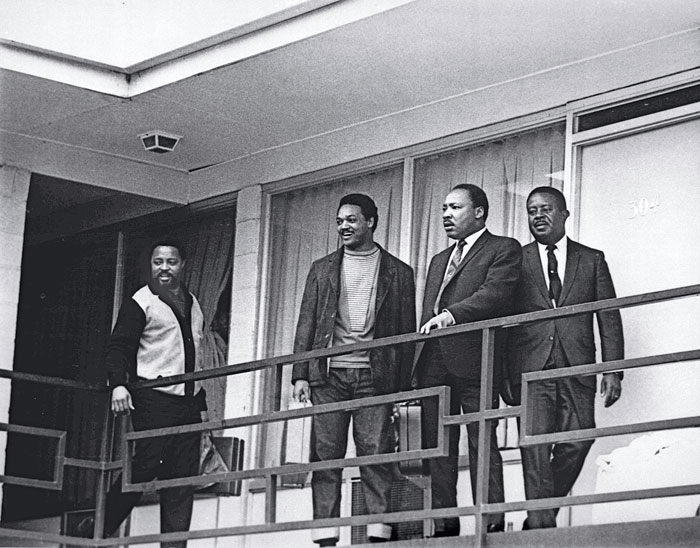

◀ By 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. (second from right) realized that true freedom could come only with economic equality. He began a Poor People’s Campaign. He went to Memphis, Tennessee, to support striking garbage collectors, and was shot to death on the balcony of his motel.

In 2011, a 30-foot-tall stone sculpture honoring Martin Luther King Jr. was dedicated in Washington, D.C. The sculpture’s name, the Stone of Hope, comes from a line in his “I Have a Dream” speech: “With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.” It is the only memorial on Washington’s Mall that doesn’t honor a war, a president, or a white person. ▶

◀ Malcolm X, born Malcolm Little, was a member of the Nation of Islam. That group believed whites were racist “devils” who would never change, so there was no point in fighting for civil rights. Instead, the Nation of Islam urged African Americans to keep to themselves and work for their own betterment. But then Malcolm went to the Muslim holy city of Mecca, in Saudi Arabia. He met Muslims of all races, and he changed his anti-white position. He even went to Selma to speak. Three weeks later, on February 14, 1965, he was assassinated, allegedly by a group that disagreed with him. Even after his death, Malcolm X inspired millions to think in a positive way about their African heritage and African American culture.

Check It Out!

What were the long hot summers?

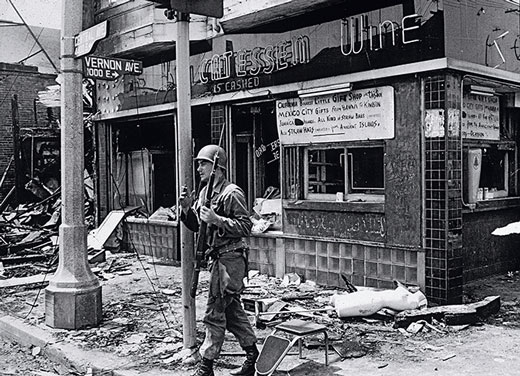

The civil rights movement raised the hopes of many African Americans that they would finally be treated fairly in the United States. But some were so angry about centuries of oppression that they couldn’t join a nonviolent movement. From 1964 to 1968, riots broke out in black neighborhoods in many cities. These included Harlem in New York and Watts in Los Angeles. Those summers became known as the “long hot summers.”

Check It Out!

Who were the Black Panthers?

By the mid-1960s, some African Americans thought the civil rights movement had done all it could with its nonviolent strategy. They took up the slogan “Black Power.” That could mean economic power, political power, or the power of weapons. The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense believed African Americans had the right to bear arms for self-defense against police brutality. They also did community organizing and ran a free breakfast program for poor children.