Free

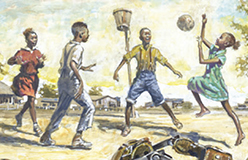

Wilma Rudolph beat polio to become a champion athlete – first, a basketball star, then a runner.

About her running ability she said, “I don’t know why I run so fast; I just run.” And run she did – all 5 feet 11 inches of her. Though her records have since been broken, in her day, Rudolph was known as the fastest woman in the world – and she was.